And our partners are on the stage too, more than just members of the audience, fully participating in this stardom-through-testing. We bring you yet another exciting instalment from our fascinating show-and-tell real-world Aflasafe demonstrations with farmers in Burkina Faso. This time, the thrilla in Burkina is a trip from the field and back to the lab. Having already brought you indicative field results from the final months of 2018, we’ve taken the next precision step we promised: top-notch laboratory testing to re-confirm the effectiveness of Aflasafe BF01. By so doing, stepping out with our partners all along the way, we build farmer confidence, and provide a body of concrete evidence to wow partners and potential buyers on the anti-aflatoxin wonders of our product. And we’re already building relationships with the business community. Do read on!

During 2018, we reported on our farmer-managed Aflasafe BF01 demonstration plots created with groups of farmers, organised either through farmer organisations or private companies, across 10 different sites in seven provinces of Burkina Faso. At harvest time, in October and November, we worked with our farmer partners to test maize and groundnut samples live in the field at several of these sites – comparing Aflasafe-treated and untreated plots for live proof of Aflasafe’s effectiveness, as well as giving farmers a chance to see and try their hands at the testing process. But even then, the story still wasn’t over – in January and February 2019, it was back to the lab for a final round of testing and analysis.

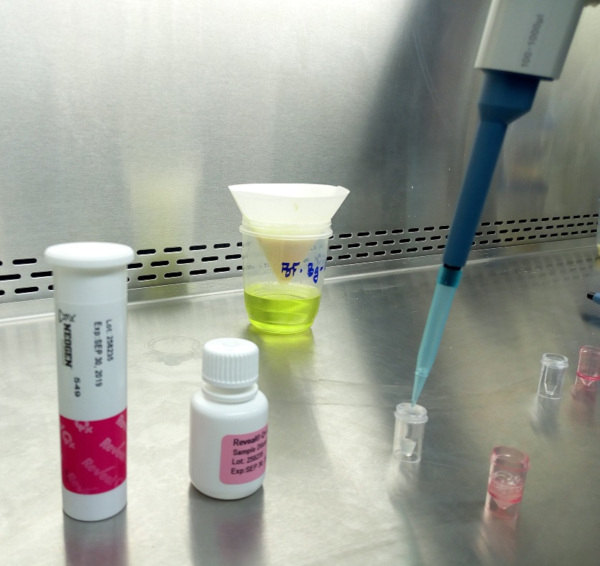

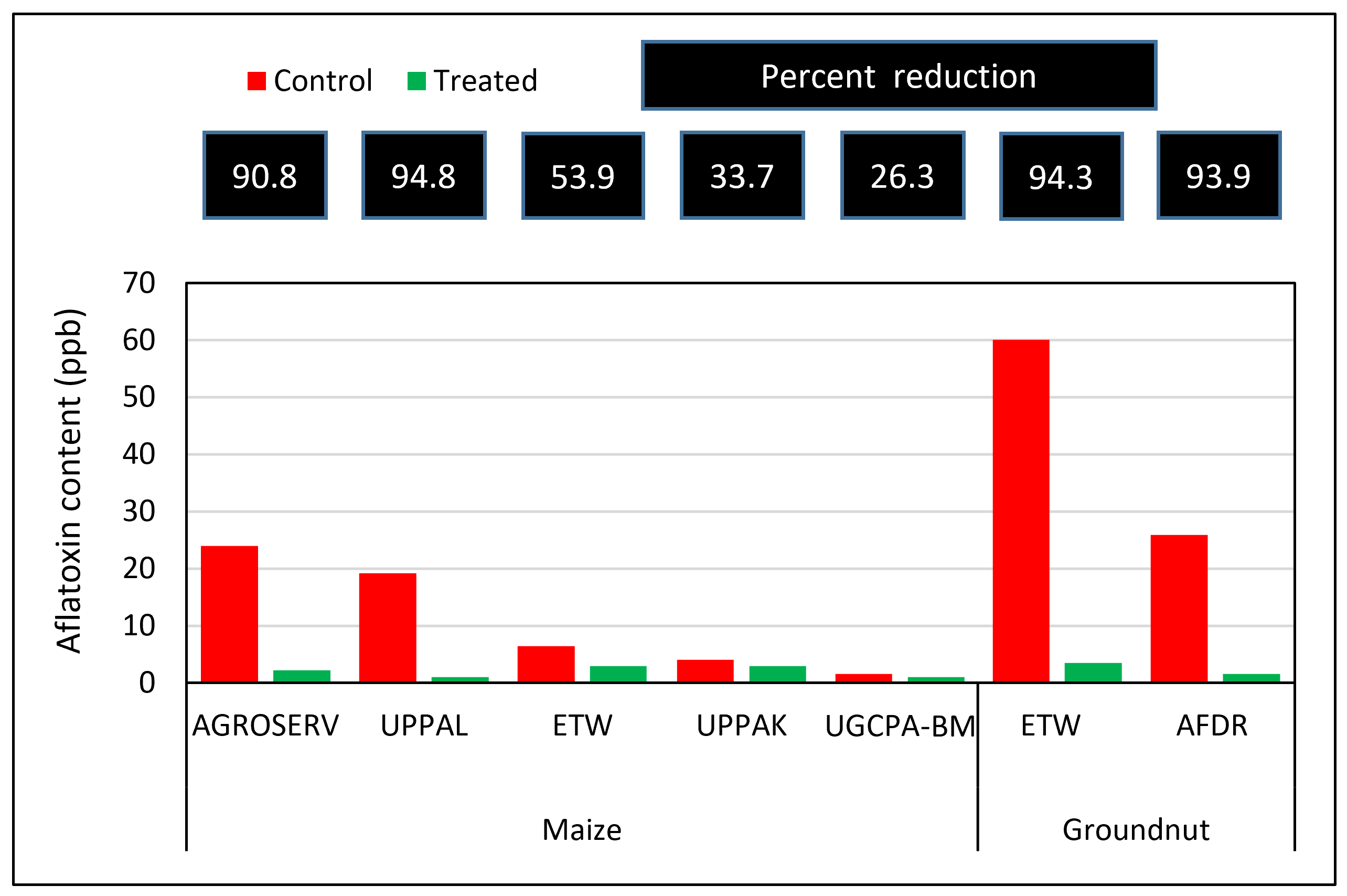

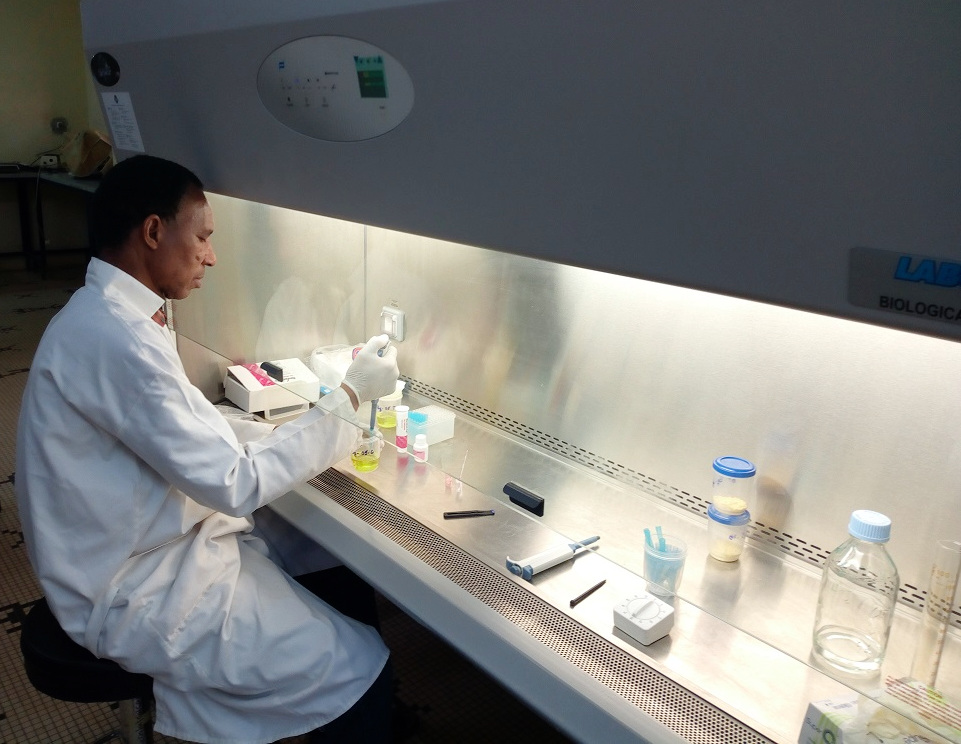

The samples were tested to measure their total aflatoxin content (including the B1, B2, G1 and G2 types of aflatoxin) at the plant pathology laboratory of the Farako-Ba Research Station of Burkina Faso’s Institut de l’Environnement et de Recherches Agricoles (INERA), our long-term collaborator in the development and commercialisation of Aflasafe BF01. You can see the results in the graph below, grouped according to partner organisation.

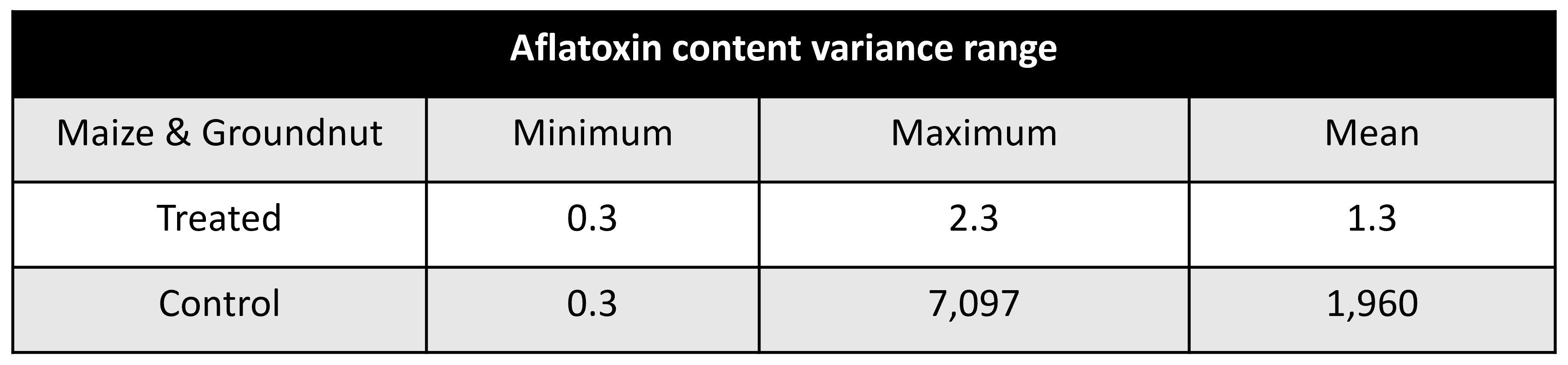

Even at first glance, it’s clear to see that Aflasafe BF01 ensured aflatoxin contamination was consistently low in both maize and groundnuts across the different sites, whereas toxin levels were much higher and more varied without treatment. These wildly unpredictable aflatoxin levels mean that, without Aflasafe and other good agricultural practices, farmers essentially play roulette with their harvests from year to year and field to field, never knowing whether they will be safe to eat or worth trying to sell to high-paying buyers, while companies working with groups of farmers find it impossible to guarantee a reliable supply of aflatoxin-safe products. A way of measuring this is the variance of the data, shown in the table below, which is much higher in the samples from the untreated than the treated fields. Aflatoxin contamination even varies from plant to plant and grain to grain, making it difficult to get a meaningful overview, but we take our samples from across the whole plot to get the best snapshot we can.

So how did these scientifically analysed post-Aflasafe results compare with our live tests from the field? “The field and lab results are essentially the same,” says Dr Adama Neya, INERA Plant Pathologist. “There were a few small discrepancies, since there is more risk of contamination when testing in the field and we are under time pressure, while in the lab we are working in controlled conditions. But overall, the lab results are a powerful confirmation that the field testing works. It gives us definitive data that we can report back to our demonstration partners with even more confidence, to support the field results and provide even more proof that Aflasafe fights aflatoxin effectively.”

In groundnuts, for example, the average aflatoxin levels in Aflasafe-treated plots were just 3.5 and 1.6 parts per billion (ppb) at the ETW and AFDR sites respectively (see the graph caption for the full names of partners) – well within the limits that are safe to eat and desirable for buyers. The lowest level in any plot was 0.6 ppb, and the highest was 5.3 ppb – in other words, Aflasafe reliably does an excellent job – reducing aflatoxin by around 94% – so that the amount of contamination is always low and doesn’t vary much. In the untreated fields, in contrast, the average aflatoxin levels were 60.1 and 25.9 ppb, dangerously high for anyone eating these groundnuts, especially on a day-to-day basis like the farmers we work with, for whom they are a staple food. The least contaminated sample had only 0.2 ppb, but the worst had a chilling 194 ppb of aflatoxin.

To make sense of these numbers, safe limits in food are usually considered to be around 4–20 ppb, and sometimes even lower for special uses such as baby food. The European Union, for example, bans imports of maize and groundnuts with more than 4 ppb of aflatoxin if they are intended directly for eating, while the USA allows imports with up to 20 ppb in most foods. In Africa, both Ghana and Kenya consider up to 10 ppb of aflatoxin in food to be safe, while Nigeria has a safety level of 4 ppb. The average levels of aflatoxin we’re seeing in untreated samples are harmful to health, and would prevent most of the harvests being sold for good prices for regional or international export, while Aflasafe keeps the levels of aflatoxin low.

The story is similar for several of the maize sites. Where we worked with Agroserv and UPPAL, the average levels of aflatoxin contamination were 23.9 and 19.2 ppb, and many samples were unsafe, with the worst containing 136 ppb. At these sites, Aflasafe BF01 cut down on the toxin by more than 90%. At the ETW, UPPAK and UGCPA–BM sites, aflatoxin levels were low in 2018 so even the untreated samples tended to be safe, but Aflasafe nonetheless helped reduce the amount of toxin. Overall, every single maize sample from Aflasafe-treated plots had less than 4 ppb of aflatoxin – except for a single field with 4.8 ppb.

This is great news for farmers hoping to sell part of their maize for a good price, as well as eating safer food themselves; the national Burkinabe brewery Brakina, for example, which uses large quantities of maize grits to make beer and is the country’s biggest buyer of aflatoxin-safe maize, has an aflatoxin limit of 4 ppb in place. Farmers organisations are also planning to bid to supply the national SONAGESS (Société Nationale de Gestion des Stocks de Sécurité) and regional ECOWAS food reserves, which have similar strict aflatoxin limits in place, and are eager to take advantage of the new opportunities opening up to them.

Some of the farmers we work with have already suffered the financial pinch of aflatoxin. Baguéra, where we worked with farmer organisation UPPAL, is an aflatoxin hotspot. In 2012, around 500 tonnes of maize that had been sold to the World Food Programme were rejected due to high levels of aflatoxin contamination. Well aware of – or still smarting from – this, many farmers in the group were very keen to implement demonstration plots in their own fields so that they could practise using Aflasafe, and produce high-quality aflatoxin-safe maize both for sale and for their families.

As well as confirming the field results, another reason the laboratory testing was so important was that not all the samples collected from the demonstration plots last year could be successfully tested on site. At many sites, we were able to show farmers the power of Aflasafe with live testing, but at some, we could not do the tests there and then due to various technical problems: either because power generators failed or because we did not have a clean, disinfected work area to prevent contamination of samples and equipment that might have corrupted the results. By testing in the lab, we therefore make sure that we get a full data set with results from every single demonstration plot – that no sample is wasted and no information is lost.

Dr Neya and his team have ambitious goals, and are already organising ahead to make sure that this year’s samples can be tested both in the field and in the lab – avoiding testing failures by for example transporting their own generator or ensuring they can create an appropriate work area with a full bleach-clean, and grouping neighbouring sites for time-efficient testing days. Meanwhile the lab testing will continue to act as both confirmation and backup. Dr Neya also has innovative plans to invite lead farmers to Bobo-Dioulasso to witness the samples from their own village being tested as even more powerful confirmatory follow-up to the field results.

“All of this – both field and lab testing – is very much about building confidence between us and farmers. That confidence is everything,” says Dr Neya. “We share all of our results with them and we help them to see the power of Aflasafe with their own eyes as much as we can. This way we are building partnerships based in deep mutual trust and cultivating a firmly convinced, enthusiastic corps of Aflasafe ambassadors for Burkina Faso.” Not only are the laboratory results extra reinforcement for the partners we’re working with on the ground, but they make a body of evidence and a nationwide overview that we can share more widely. Taking a little peek ahead to the start of quarter two, on 12 April 2019, we held a workshop to present the results. We welcomed all the farmer organisations and companies that we’ve been working with on the demonstrations, including Agroserv, which processes maize into flour for sale to shops and to SONAGESS and into grits for Brakina for beer production. We also went further in spreading the word, inviting several other companies that also struggle with aflatoxin contamination in Burkina Faso, and are therefore potential buyers of Aflasafe-treated maize or groundnuts. These included key staff from Brakina, Econut, a startup planning to process groundnuts for sale in Burkina Faso and for export, and InnoFaso, producers of highly nutritious foods for exclusive sale to UNICEF to treat severe and acute malnutrition, particularly in children – the health consequences of aflatoxin for babies and children are a big concern in Burkina Faso, where 84% of cereal-based infant formula produced in the country has been found to contain aflatoxin B1 (the most toxic type), at up to hundreds of times the safe limit.

For the farmers, it was a chance to compare the results from their own villages with those of others, and to see that Aflasafe works consistently across different locations, crops and conditions. Many mentioned that they were even more convinced than before, and even more eager to buy Aflasafe. For the company representatives, meanwhile, it was an insight into a promising solution to a perennial lethal problem that won’t just go away by itself but needs active intervention that works. For both groups, there was a compelling argument and objective verified evidence on Aflasafe’s effectiveness. The Brakina representatives, for example, were very happy to know that there is now a tool to help farmers reduce aflatoxin contamination right from the field, before they sell their maize. It was also a chance to meet and organise business-to-business meetings with our new distributor, SAPHYTO SA – more on that in the next issue!

“This gives us something to show; something we can talk about,” says Dr Neya. “It is crucial that we build awareness of Aflasafe BF01 and spread the knowledge of how and why to use it. These real-world results give us the concrete proof that Aflasafe works, and help us show that it’s the solution that both farmers and buyers are looking for.”

All this fits right into an exciting and transformative project that is in the works, focusing on public health, international food safety standards, access to local and international markets, and raising incomes for Burkinabe farmers while protecting consumer health. It will be funded by The Standards and Trade Development Facility (STDF; in French, Le Fonds pour l’application des normes et le développement du commerce) and is entitled Réduction de la contamination du maïs et sous-produits à base de maïs par les aflatoxines au Burkina-Faso, Afrique de l’Ouest (ReCMA–BF).

LINKS

- Previous news items from us:

- Royal ambassadors for Aflasafe BF01: Kings join the fight against aflatoxin in Burkina Faso (English | Français)

- Market-testing in Burkina Faso exploring Aflasafe BF01 commercialisation

- Marketing Aflasafe BF01 in Burkina Faso – Big plans from a big name

- Bright aflatoxin-safe days ahead as Aflasafe BF01 is launched in Burkina Faso

- What next after Aflasafe BF01 registration? Aflasafe means business in Burkina Faso

- Keep up with the latest on Aflasafe in Burkina Faso