Chronicles on a big problem, and a broad solution

Flashback: In early 2015, Kenya’s National Irrigation Board (NIB) purchased Aflasafe to help deal with aflatoxin contamination in maize, a predicament afflicting some of its irrigation schemes. For example, in most years, the UN’s World Food Programme was unable to purchase maize from Hola and Bura owing to excessive aflatoxin. Fastforward to 2017: What were the results of this NIB purchase then, and today, two years on? Read on!

The facts and figures speak for themselves. The naturally occurring poison – aflatoxin – is hardly new in Kenya, and has long haunted the country. Aflatoxin has resulted in deaths, widespread contamination of food, animal feed and milk, and destruction of maize. Some of these incidents have been widely reported in the media through the years. What is relatively new, and not as broadly reported, are successful efforts to combat aflatoxin, with the government as a key actor. Efforts that once expanded would halt the recurring painful trend and its toll. And save lives – literally.

In 2015, the government earmarked a sizeable KES 1.5 billion to fight aflatoxin and also initiated the one-million acre Galana-Kulalu Food Security Project in Tana River County. NIB seized the opportunity to apply Aflasafe on a large scale. “Earlier in the year, we’d airfreighted 8.2 tons of Aflasafe and used it for the entire crop sown in May,” recalls Dr Raphael Wanjogu, NIB’s Chief Research Officer.

The result? Dramatically reduced aflatoxin, whose contamination is measured in parts per billion (ppb). That first year, in Galana, all the Aflasafe-treated maize had less than 4 ppb, meeting not only the Kenyan regulatory threshold of 10 ppb, but also the even more stringent European Union standard of 4 ppb. The maize was safe to eat at home, and was also a premium product that could be sold anywhere abroad – the US aflatoxin threshold is 20 ppb.

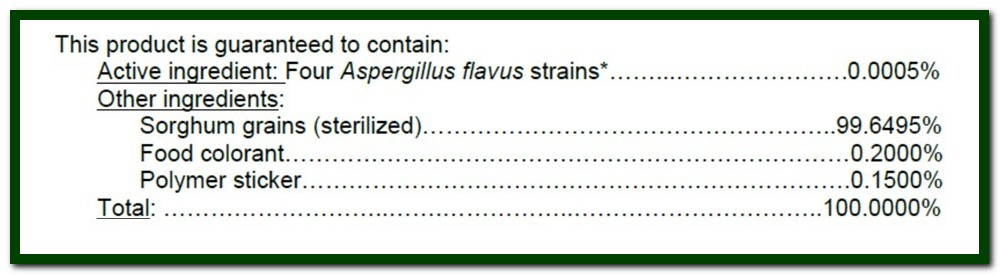

But what is Aflasafe and how is it made? It’s an environmentally friendly solution to aflatoxin, green in branding, as in deed, and indeed. A full 99.7% of the product is actually just sorghum grains.

To prevent germination and stabilise the product, the sorghum is ‘killed’ by heating before coating with spores of four native-to-Kenya friendly fungi of Aspergillus flavus (A flavus). Friendly because unlike their toxic aflatoxin-producing cousins, these beneficial fungi are types of A flavus that cannot ever produce aflatoxins. Instead, owing to the playing ground being deliberately tilted in their favour numerically, the fortified and amplified ‘army’ of beneficial fungi once unleashed and ‘deployed’ in the field progressively displaces the outnumbered and outgunned poisonous types of A flavus, thus creating a cumulatively safer environment for the crop, season after season.

Multiple studies have shown Aflasafe consistently reduces aflatoxin contamination in maize and groundnuts by between 80 and 99 percent at harvest and in storage. Applied preharvest but with postharvest benefits, a single application of Aflasafe – just this one single action in each cropping season − is all that is required to protect maize or groundnuts along the entire pipeline from plot to plate.

Since the soil is home for aflatoxin-producing fungi, contamination while the crop is still in the field is irreversible, even with proper drying and storage after harvest. While these good practices can and do arrest the increase of aflatoxin after harvest, they cannot however ‘cure’ the pre-harvest contamination. This, Aflasafe can, by reducing or preventing aflatoxin contamination in the first place while the crop is still in the field. And as the adage goes, prevention is better than cure. “Some of our contracted farmers took long to harvest their Aflasafe-treated maize, and it got rained on in the field after maturity. And yet, when we tested it, it was still within the safe threshold for aflatoxin. We also tested the treated maize in storage and found no contamination,” reveals Dr Wanjogu, re-affirming Aflasafe’s all-round aflatoxin protection, when coupled with good agricultural practices.

So how was Aflasafe developed? In and out of Africa, through cross-Atlantic and inter-African partnerships. In faraway American shores, the Agricultural Research Service of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA–ARS) invented a natural, safe and cost-effective method to counter aflatoxins. Thereafter, across the Atlantic in Africa, the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) worked with USDA–ARS and several national partners in Africa to adapt and improve this technology for Africa. The result? Aflasafe. In Kenya, the main national partner was the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO). Aflasafe KE01™, the name by which the Kenyan product is identified having been made from fungi native to Kenya, was officially launched in October 2016. KALRO is the registrant and will pioneer manufacturing Aflasafe KE01 at its plant at Katumani, Eastern Kenya. Local production will commence in 2017. The product NIB airfreighted to Kenya in 2015 was still Aflasafe KE01, but manufactured at IITA Headquarters in Ibadan, Nigeria.

NIB collaborates with IITA and the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries. “Based on our positive experience with Aflasafe, the Ministry ordered an even larger consignment of 228 tons for nationwide distribution,” says Dr Wanjogu. Regrettably, due to a searing drought in some of the target Counties, some of the product could not be used for the anticipated sowing season in April 2016. However, in Galana, thanks to irrigation, NIB used Aflasafe on 3,500 acres in three successive seasons from 2015.

“I first learnt of Aflasafe from Charity Mutegi,” says Dr Wanjogu. Dr Charity Mutegi is IITA’s Aflasafe Coordinator in East Africa. “Aflatoxin had long been a problem for our farmers, even after they dried and stored maize properly,” Dr Wanjogu laments. “It was painful to see farmers suffer huge losses and have their crops incinerated, which is what drove us to search for solutions. We started working with Charity on Aflasafe trials in farmers’ fields in Bura and Hola in April 2012. We witnessed progressive reductions of about 90 percent in the first and second seasons.”

Impressive, right? But Dr Wanjogu is quick to qualify this apparent success a wise word of caution as a reality check. It all depends on the starting point: “Some areas had upwards of 1,000 ppb! With such high contamination, there can be no immediate solution or quick win. Rather, the gains are progressive and gradual.”

In April this year, NIB milled and sold their first aflatoxin-safe maize flour at no profit, recovering only production costs, and therefore at a lower price than the market (KES 75 per 2-kg packet, less than half of the commercial price of KES 153 at the time). “Consumers say it’s tastier,” says Dr Wanjogu.

But despite this rosy picture, the going has not always been easy, and there have been bumps along the road. There were those who were sceptical and pessimistic, saying that Aflasafe would not work,” Dr Wanjogu recalls. “And then, we had not budgeted for that first consignment we ordered from Nigeria. So, we had to apply for emergency and special exemptions, and airfreight rather than ship.” And for what is a cross-sectoral problem touching on agriculture, health and trade, knowledge gaps are also a problem – some know about aflatoxin and Aflasafe, and some don’t.

The potential for Aflasafe in Kenya goes beyond maize. Groundnuts and sorghum are also aflatoxin-prone. Dr Wanjogu would like to see Aflasafe use also spread to other crops to increase its benefits, but there must also be economic incentives. He adds, “Where there are no direct monetary gains for farmers, they are not interested. This contributed to our success in Hola and Bura since farmers could sell their produce. Galana demonstrates the power of irrigation and is a revolution, with maize yield averaging 31 bags per acre of safe food for Kenyans in arid and semi-arid areas.”

Dr Wanjogu sums up Aflasafe with an apt Kiswahili saying: Kizuri chajiuza, kibaya chajitembeza, which loosely translates into ‘A good product is its own best advertisement: while a poor product inevitably fails or loses’.

All Galana-Kulalu maize is Aflasafe-treated. Today, nearly all (about 99%) of the scheme’s maize is aflatoxin-safe by Kenya’s standards, while 96% meets the EU standard. Thus far, 5,910 tons of maize have been harvested (from a small fraction of the cultivable area in the scheme). Without Aflasafe, much of the maize would have been lost to aflatoxin, defeating food-security goals. The scheme’s produce has primarily been for perennially food-insecure people in the coastal and eastern regions where it is located. These were also the regions most hard-hit by the recent drought. But thanks to Galana-Kulalu, nearly half a million (492,534) of the regions’ most vulnerable people benefited from aflatoxin-safe maize for one month.

According to Dr Lusike Wasilwa, KALRO’s Crop Systems Director, by milling and marketing aflatoxin-safe flour, NIB has taken Aflasafe to the next level in raising consumer awareness. “All too often, we develop technologies which we disseminate and they die as projects die. Aflasafe is a product that works, and that saves lives,” she concludes.

Links

- Aflasafe– Overview | 5-min video (featuring Dr Wanjogu, among others)

- International aflatoxin symposium in Nairobi, March 2017

One Reply to “Successfully combatting aflatoxin in Kenya’s food with Aflasafe on a large scale”